As the calendar turned to the second decade of this millennium, and the Great Recession became an unwelcome sight in the rearview mirror of the 00s, sportsman-level heads-up drag racing felt the serious pinch of rising prices and declining disposable income.

The NMRA’s lower-level heads-up classes were suffering, with car counts miniscule and dwindling. With many racers complaining of cost concerns, it was a major issue for the series; with no racers, there is no series. The NMRA’s lower-level classes like Real Street and Pure Street – classes which had been the breeding ground for heads-up racers since the NMRA’s inception in the late 90s – disappeared due to the intense costs of competition, leaving some of the series’ most well-known racers with nowhere to go.

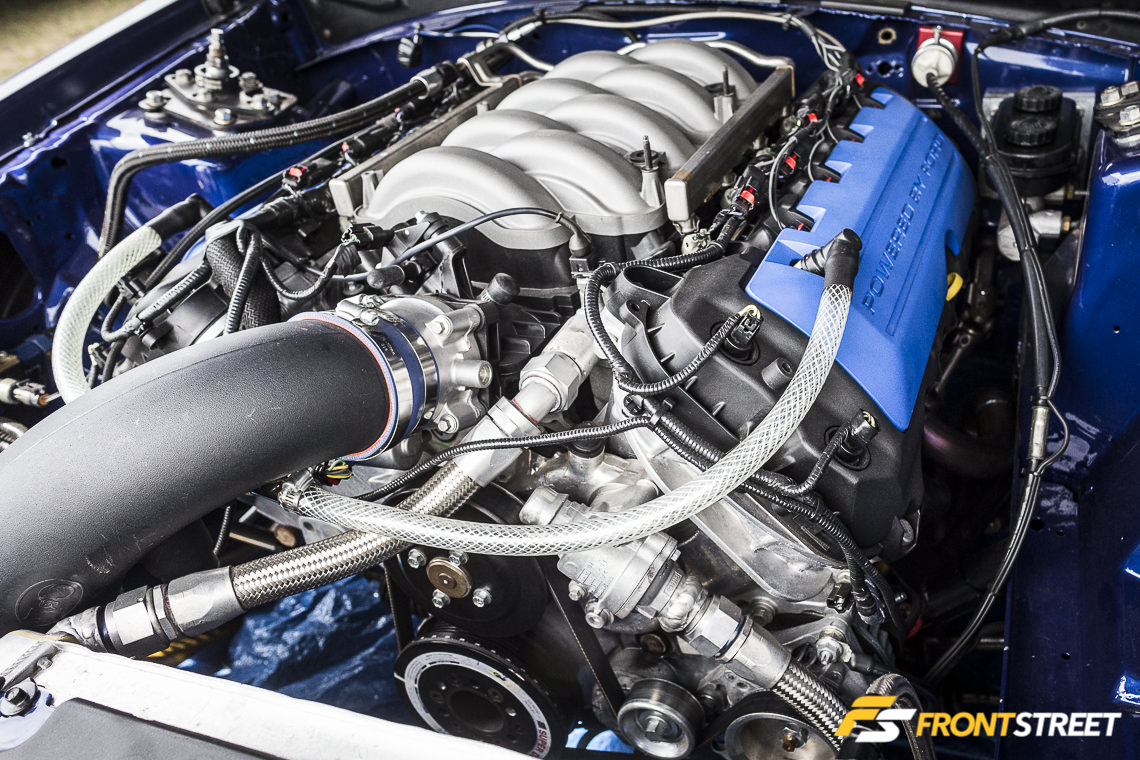

With the exception of an aftermarket PCV kit and a couple of other small modifications permitted in the rules package, these engines are as stock as the day they rolled off the assembly line at Ford Motor Company.

Then, with the release of the 2011-current Mustang’s powerful 5.0-liter Coyote engine, a light went on for two of the NMRA’s biggest cheerleaders. Former Factory Stock/Pure Street racer Steve “The Farmer” Gifford and former Pure Street racer/tuner/crew chief Ken Bjonnes began to flesh out an idea rooted in circle track racing; to build a class where engines could be sourced directly from Ford, sealed at the factory, and delivered with a Control Pack, which included an engine management processor set up with a Ford Performance “spec” tuneup. This concept had one main advantage – controlling the engine build costs as much as possible through the sealed engine and controlled calibration strategy – and leveling the playing field to where one racer didn’t have an engine advantage over another simply because his or her pockets were deeper.

Bjonnes is one of those folks who’s always thinking about ways to make things better. Perhaps that plays well into his career, where he spends hours upon hours calibrating all sorts of engine combinations and is considered one of the premier tuners of the Coyote engine today. But that wasn’t his goal when he and Gifford began talking about the idea, which has turned into the Coyote Stock class in the NMRA.

One-half of the braintrust behind Coyote Stock, Ken Bjonnes (left) and class racer Carlos Sobrino (right).

They had two goals: one competition weight and one sealed engine, making power-to-weight and driver skill the top two considerations when it came to fielding a car for their class.

With nearly four seasons of racing complete since the first event in 2012, the Coyote Stock class has finally shown the promise it offered when the lightbulb went off for Bjonnes and Gifford.

“The goal was extremely tight racing where the fastest guy doesn’t always win, to reduce rules arguments – especially between combos – and to have full fields. It took a little longer for that to happen, but we are finally there,” says Bjonnes.

Gifford, who has been the most vocal proponent of sealed-engine racing, continues to beat the drum for the Coyote Stock class to anyone who will listen. Prior to brainstorming the Coyote Stock idea with Bjonnes, he spent vast sums of money trying to stay at the head of the pack in both Factory Stock and Pure Street over a decade-long career with the NMRA.

“This class has blown away our expectations. In my opinion we revolutionized drag racing; we did something they said could not be done,” says Gifford. “The reason I race this class is because of the rules. Give me an even playing field and I will kick your a**.”

Steve Gifford doesn’t pull any punches when it’s time to talk about Coyote Stock racing.

Everyone Has Something To Say: The Good, The Bad, The Ugly

Inaugural season champion Joe Charles – a racer with a wealth of experience behind him in longtime racer and partner-in-crime Tim Matherly – made the dive into Coyote Stock right away, seeing an opportunity to get into the game for a fraction of the previous cost to race in a heads-up class.

“It looked like a freaking blast! The planets just kind of fell into alignment, as the decision was very spontaneous. My wife had been urging me to get back into a car, then the class was announced so I called Tim to talk about it. In less than 15 minutes he agreed to let me “borrow” the chassis, which was just sitting in his shop. I bought the engine and controls pack. It was the first engine sold and shipped,” says Charles.

Charles won the championship with the car that first year, and turned in some of the quickest and fastest elapsed times in the class before exiting the class prior to 2016 – returning the car to Matherly in the process, who is using it in his own bid to win the Coyote Stock championship in 2016.

Matherly, who has raced in just about every Mustang class under the sun – Pro 5.0, Renegade, and Real Street among them – over a two-plus-decade run, has his own thoughts on what’s made Coyote Stock successful.

“I have always liked the idea of the class – it takes a lot of variables out of the equation and shows the talent of the driver and crew. I believe the class is stronger than ever. It’s a lot more appealing to go to a race with confidence in a chance to win versus knowing that you brought a knife to a gun fight,” he says.

Joe Charles won the inaugural Coyote Stock championship in this car; it has history as a multi-time Real Street championship-winner at the hands of Tim Matherly – who is now back in the seat, competing in Coyote Stock himself.

The 2016 season has seen Jacob Lamb – who honed his driving skills in the NMRA’s Modular Muscle class before moving to Coyote Stock – win the first two events with supremely consistent passes.

“I don’t worry about what everyone else is doing. If someone is running fast in testing that’s great, but it’s what you run on race day that matters. I have as many or more passes on my car than anyone in the class. This is a driver’s class and we have some of the best drivers around. I try to stay focused and run my race,” says Lamb.

A glance in the direction of Mike Bowen’s 1970 Grabber Blue Maverick shows that Coyote Stock isn’t all Mustangs, all the time. Bowen, who uses his experience racing to also help with development of products at his business, Powerhouse Automotive, has battled through the challenges associated with using an out-of-the-ordinary chassis – especially with no fellow racers using the same platform.

“I built a car that I’ve wanted to build for a long time. I enjoy the fact that the car is currently the only non-Mustang in the class, it really stands out and surely gets the attention of many of the fans. I get a lot of people stopping by in the pit to share stories of their dad/mom/uncle/sister that had one way back when, and all the abuse they put that car through. Some of the stories are pretty interesting,” says Bowen. “People can relate to what we’re doing with these cars.”

Mike Bowen’s Maverick blends old-school-cool with modern technology.

Doug Johnson spent a number of years competing in the NMCA’s Mean Street class before moving over to Coyote Stock, and containing costs were a large part of the motivation for the longtime racer.

“Year after year I spent a good amount of money having to refresh my engine program. With Coyote Stock the engine doesn’t need any work except making laps. The other issue is the constant change in rules for a given class – some years by the time you got a handle on your particular combo some rule change was put in place that impacted your combo or put you behind the eight ball again. It takes time, sometimes more than one season, to get your program going in the right direction. With one set of stable rules for all participants, you can accomplish this,” explains Johnson.

That’s perhaps the most appealing part of the sealed engine equation; when all competitors are placed on a playing field that has been engineered to be as even as possible, the races come down to the drivers, their capabilities behind the wheel, and their ability to dissect the rulebook and modify the cars – where possible – to take advantage of any areas where they feel there might be an advantage.

Coyote Stock is attractive to a new racer like Rob Chandler, who doesn’t have years of NMRA racing under his belt.

“Not having to chase a tune, and spend money each year on engine upgrades is attractive – it’s a heads up class I can be part of. Other classes take more time and money than I can realistically spend. I don’t have a single sponsor so everything on the car I paid for out of pocket,” says Chandler.

Gregory Herbert’s a first-time heads-up racer learning the ropes in Coyote Stock.

Gregory Herbert, who has also made Coyote Stock his first-ever heads-up racing experience, has had a monstrous learning curve.

“I would have to say our biggest challenge so far is that we are so new to heads-up racing, especially in the aspects of reading data and capitalizing on it. Slowly but surely we are figuring this combination out and making progress. In due time we will be a force to be reckoned with. One change at a time, in the right direction. And never get complacent, because someone else is always out there trying to get it done better,” says Herbert.

Over the course of twelve years, Carlos Sobrino’s name became virtually synonymous with the NMRA’s Factory Stock class – until Coyote Stock came around. But for Sobrino, it wasn’t necessarily a cost issue to make the change into the new class.

“What attracted me the most to Coyote Stock was the slick tire – like most racers my age, we started racing before drag radials even existed. The continued maintenance and research and development associated with heads up racing had no bearing on my switching. But I quickly found out that you’ll spend the same if not more money on a sealed motor class cause it’s still heads up racing.”

Brandon Alsept spent untold thousands of dollars to win in Pure Street, but when Coyote Stock came along he made the switch to the class.

Brandon Alsept is a former Pure Street World Champion who made the decision to step into Coyote Stock after his life priorities changed.

“For me Coyote Stock came around just at the right time. I was looking to find something a little cheaper and less time consuming than Pure Street had been. Don’t take this as Coyote Stock is a cheap class and doesn’t require time – but it is, in comparison to the effort and expense of Pure Street,” says Alsept.

“It offers me the ability to still race against some of the best the NMRA has to offer – the competition is fierce as ever and that is what should drive any racer – to want to race and test yourself against the best.”

Walter Baranowski originally had plans of joining the NMRA’s Renegade class, but a trip to the World Cup Finals at Maryland International Raceway where he was introduced to some of the class competitors changed his mind quickly.

“After watching and talking with Carlos a lot that weekend, I decided to sell all my old stuff and go Coyote Stock racing,” says Baranowski.

Recent high-school graduate Tyler Eichhorn is a second-generation NMRA racer, as his father Tim had years of experience in the old Hot Street class. Ironically, the duo spends all day building engines at Mustang Performance Racing in Florida – but chose a sealed-engine class to help the youngster get his feet wet.

“It is basically a driver’s race, and being a rookie I have a lot to learn,” says Eichhorn.

“Our biggest challenge is that I can’t drive – I am still learning how to hit the shift points on the dot. A lot of guys in the class are teaching me what not to do and how to drive the car. I love the opportunity of running with a great group of people – they feel like family, filled with drama and constant trash talking, but that’s the fun part.”

Tyler Eichhorn (left) and Tim Eichhorn (right) are applying the lessons Tim learned as a Hot Street racer to Tyler’s Coyote Stock program.

Citing cost and equality as near-equal factors, Mike Washington made the change to Coyote Stock after years of racing in Factory Stock and Real Street.

“Without spending the money on the engine to compete at the levels in restricted class racing, I was able to push the envelope on chassis development and driving skill. The old adage ‘to be the best, you must beat the best’ holds true in this class. Winning is never easy, but when you have 7 World Champs to possibly weave through on elimination day, winning is that much sweeter,” says Washington.

Ken Duphily agrees, noting the level of competition as one of the major attractions to building a Coyote Stock car.

“The fact that there are multiple previous class champions to race against gives you the opportunity to see how you stack up against some great drag racers that have been in the game a long time. I’ve followed the NMRA since the early 2000s and always wanted to give it a shot – Coyote Stock was the best opportunity to do so,” he says.

Coyote Stock has attracted longtime NMRA racers like John McGowan (left) and Michael Washington (right) to its ranks.

There are also a number of competitors who are in the process of building cars to debut later this season, among them Mike Nisi, Jr. and Joshua Alwardt, both of whom agree on the controlled costs as a large part of the attraction to the class. Alwardt, who worked as crew on his father’s NMRA Street Outlaw program, understands the challenges of a cost-no-object class.

“After being crew for Dad’s car for so many years, and seeing how much money he put into his car, the idea of the core of the race car being a sealed even playing field was what drew me in. I’ve learned there’s a lot more to having a front running car then slapping the motor in and going,” says Alwardt.

Nisi, Jr. says he’s faced a number of challenges getting the car together, but should be ready for the race at Route 66 Raceway later this summer.

“I have done most of the work on the car by myself, only farming out the roll cage, paint and body, and the rear end. I’d like to thank Jacob Lamb, who has been a wealth of knowledge,” says Nisi, Jr.

“The class comes down to hitting the right combination of clutch, and suspension setup and also the ability to cut a decent light. It’s really one of the only heads-up classes that you can run that’s affordable for the little guy.”

This sentiment is echoed across the board by every competitor we spoke with; although it’s very easy to get sucked into the program and drop plenty of money on the latest whiz-bang parts, a racer can also be competitive with smart shopping and the right knowledge.

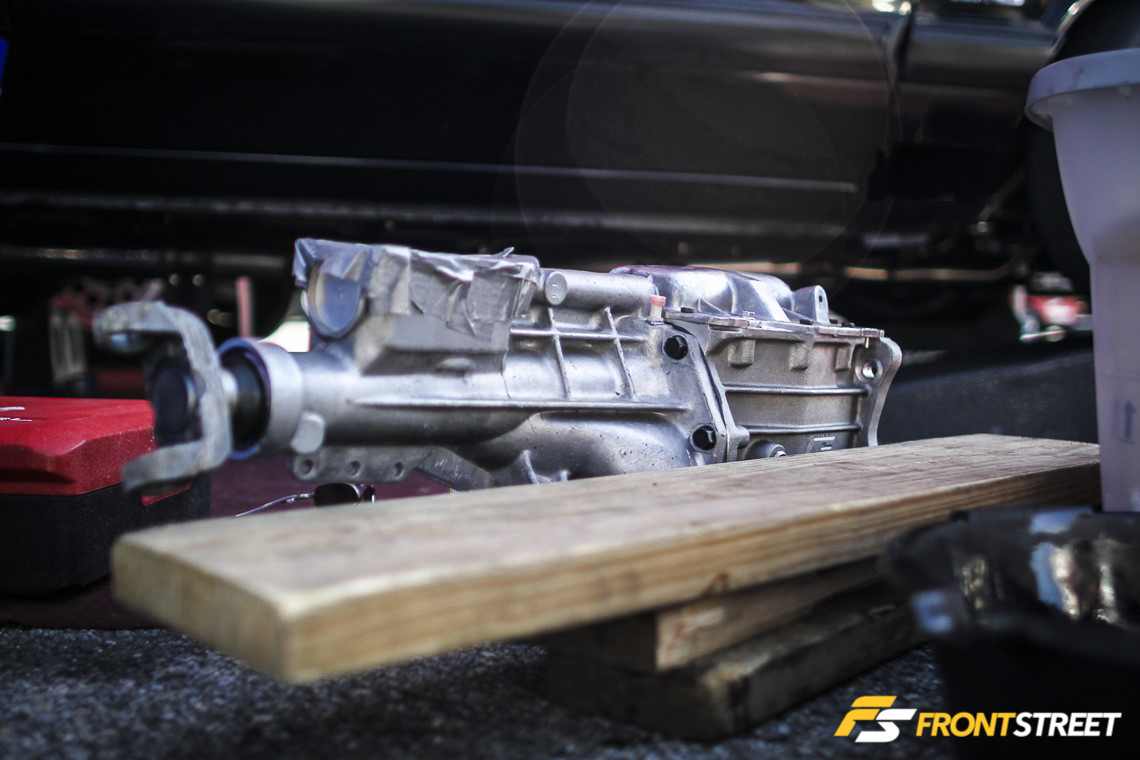

Transmission Woes: Are They The Weak Link Of the Class?

This is a common sight in the Coyote Stock pit area; the street-based transmissions simply don’t hold up to the high-rpm launches and no-lift shifting.

One big challenge for all of the racers in Coyote Stock is the challenge of keeping the transmission alive. As the class has its roots in the defunct Real Street and Pure Street rules, the initial thought of permitting five-speed transmissions like the T5 and Tremec TKO has kept the competition close. But as elapsed times have dropped and the class has advanced, keeping those transmissions alive has become a monstrous task for the competitors, as the transmissions don’t live long at the shift points where the engines are happy.

“I’m hoping we can go to a better more durable transmission like the G Force G101R. With the cars going faster the Tremec transmissions seem to be breaking more often. I know myself I broke two of them in Florida. It is hard to get parts for them,” says Rankin.

Sobrino concurs. “The main argument is that we already have a large selection in the rules to choose from. But they’re all just modified street units and this class is way past that. Right now the transmission is the weakest, most expensive and most frustrating part due to parts unavailability.”

Parts availability for the transmissions has been challenging, so having a spare unit is a must.

Learning the challenges of the clutch setup has been a major stumbling block for some of the less-experienced competitors.

“This is a driver’s class which forces everyone to focus on their driving skills, clutch setup and the chassis tuning since everyone in theory is at the same power level. Since this is my first stick-shift race car the clutch setup has been a huge challenge,” says Frank Paultanis.

Like many of the other racers in the class, Jacob Lamb would like to see a better transmission option permitted.

“The Tremec TKO and T5 transmissions are great, but it’s time for us to step up to a better race-style transmission,” he says.

For Frank Paultanis, learning how to make the clutch work has been a steep learning curve.

Manufacturer Involvement: Ford Performance Is On Board

Jesse Kershaw of Ford Performance stepped in to discuss Coyote Stock from his perspective, as without his support the class may never have come to fruition.

Front Street: Would you deem the Coyote Stock program a success by the metrics you’d use to measure it?

Jesse Kershaw: Absolutely. We’ve sold about 50 sealed Coyote engines with most going to NMRA racing. By having it available other series picked it up as well including an off-road class out west.

FS: On sealed engine racing in general, do you feel that it’s a growth opportunity? Sealed engine racing has been very popular in equalizing some of the dirt track competitions all over the country.

JK: Sealed engines provide one area in that class that can be controlled for cost. With Coyote Stock by including calibration the failures are minimal. Having a top end for cost defined helps keep racers on the track and helps put the success in the hands of hard work and talent instead of the biggest wallet.

FS: Where do you see it going in the future? I have heard that there’s a shortage of engines, do you care to comment on the plan to address this?

JK: The one issue with using a production engine is that they change over time. We’ve had a solid four seasons of hardcore competitive racing in Coyote Stock. Now the Mustang engine has changed enough that it’s making a little more power. As a result we’ve put a hold on the older 2011-2014 style engine and will only release them for Coyote Stock racers. This should get us through 2016. At some point we will need to seal a newer engine if we are to keep the cost in check but this brings up a balance of power situation. I know it’s not popular to have a balance of power but it’s going to be a reality and NMRA/NMCA has always done an excellent job finding equity among imbalanced performance. There is not complete equity between brands ever so balance of power and production based go hand in hand but the minimized cost and added marketing benefit of using real parts more than outweighs the detriment of having to enforce rules.

I would like to see more sealed engines gain acceptance in drag racing. There’s opportunity to bring value to the racer.

The Drama: Will Semi-Sealed Engines Damage The Respectability Of The Concept?

Shane Stymiest, who entered the class for the third race of the inaugural season, went on to win the 2013 and 2014 class championships before giving up the top spot to Drew Lyons for 2015. Stymiest, who runs out of the Booze Brothers camp in Pennsylvania, was initially attracted to the class because of the sealed engines.

Two-time class champion Shane Stymiest is concerned about the recent decision to allow competitors to break into the sealed engines to install new oil pumps.

But Lyons was permitted to race – and win – at the Bradenton 2016 event with an engine that had been rebuilt over the offseason by Chris Holbrook Racing Engines in Michigan. The engine had previously become unserviceable due to an oil pump failure, and Lyons was directed to have the engine rebuilt by Ford Performance, which created a difficult situation for all involved.

“When my oil pump failed, I fully expected that a new engine would be in my near future. Due to a very limited number of remaining sealed engines and no firm plans for allowance of a sealed 2015 Coyote engine, the rebuild seemed like the best option at the time. If I had anticipated the controversy though, I would have done everything in my power to avoid it,” explains Lyons.

“I still firmly believe that if people understood all of the facts, and not just listen to internet hearsay, they would understand why NMRA, Ford, and I landed in that situation.”

“The class is definitely not the same,” counters Stymiest. “The parties involved opened up a big can of worms that we all feared. I don’t blame one person – I blame everyone involved, period.”

Chalie Rankin agrees. “I worry how they will handle the lack of sealed motors and how the rebuild program will affect the class moving forward. Keeping an even playing field with the motors is key,” he says.

2015 class champion Drew Lyons has been at the center of controversy this year.

“After grenading my engine, it seemed like the most economical and quickest way to continue racing heads up. The idea of a sealed engine that I didn’t have to replace valve springs every few events, and didn’t have to freshen up the short block every year was a huge reason I made this switch,” says Matt Williams.

He has concerns as well about the current program of permitting competitors to replace their OEM oil pump with a Ford Performance unit under the close eye of the NMRA’s Technical Department.

“The only reason these engines seem to fail is due to the cheap oil pump gears which thankfully they are allowing us to upgrade now. Moving forward, if they do not allow a rebuild and the racers are forced to buy a 2015 sealed engine and control pack, I feel that many will head towards other classes,” says Williams.

Nate Stymiest – Shane’s brother – has also been hard at work getting a car together to run in the class, but has been put off by the concern of the engines having the seals broken.

“Do I think the authorized/unauthorized engine rebuild has changed the perception of the class, 100-percent, absolutely without a doubt it has! If I’m the slowest guy out there because I suck, well that’s fine. I can suck when we are all on the same playing field, but at least it’s fair,” says Stymiest.

Nate Stymiest purchased this car from former competitor Kermit Buffington and had Charlie Booze, Jr. prepare it for Coyote Stock action with some of the Booze Brothers Racing tricks which have made Shane Stymiest so successful.

Jason Henry – who lent Nate Stymiest his car to drive at the Maryland stop on the tour last year – agrees.

“The engine is the cornerstone of the class and once you disrupt/question this you have no house. For my own personal goals I hope the class does stick around and I get the chance to attend more events. But there will only be one way to know the future of the class and that will be shown by the attendance in future races,” Henry says.

Class newcomer Mike Stouffer has plenty of NHRA bracket racing experience to draw upon regarding the concept of rebuilding the engines.

“I am really concerned with how the whole rebuilt engine issue in Bradenton was handled. I have seen firsthand where there were rules infractions pertaining to Stock Eliminator engines in NHRA, where the points earned at an event were vacated and a suspension was imposed for violations,” he says.

And Bjonnes, as one of the inventors of the class, also has a well-formed opinion on the topic.

“I think it presents huge issues and I have a huge problem with it. As far as I’m concerned, I’d prefer they change the name of the class if that is the direction it’s going to take. The entire foundation of the class is a sealed engine, no rebuilds. Break it, buy a new one. Once you change that foundation, one of two things happen. Things come crumbling down, or they morph into something completely different. The changes proposed in CS open that can of worms that we have been pretty good at keeping a lid on up until this point,” he says.

The NMRA’s Coyote Stock class has it all – drama, controversy, a bit of infighting between the competitors – and some of the closest racing the NMRA has ever seen, in a class where costs have ultimately been contained as much as possible. With elapsed times knocking on the door of the 9-second zone, wheels-up launches on nearly every single pass, and a model designed to be sustainable, only time will tell if this class continues on its path to reform sportsman heads-up drag racing.